The impact of people's actions vs. intentions

3-minute read

Welcome to another study of the month (SOTM). Building on our last SOTM which explored our tendency to misread people’s attitudes towards us, I want to share with y’all a study that shocked me.

Many of us work in an environment with a bias for action over intentions. There are a number of reasons for this, including a hyper-emphasis on efficiency and productivity, a general distrust of human nature (“road to hell is paved with good intentions”), and a concern that a focus on intentionality leads to inaction.

The internet is chock-full of articles about why we should not care about intentions. What matters, the argument goes, is behavior and systems, everything else is just noise.

Yet what does research actually say about this? Are our brains affected by perception of intentionality? If so, in what way? These are questions that a group of researchers led by Kurt Gray explored in a series of studies on how our perception of intentionality impacts our experience in the world.

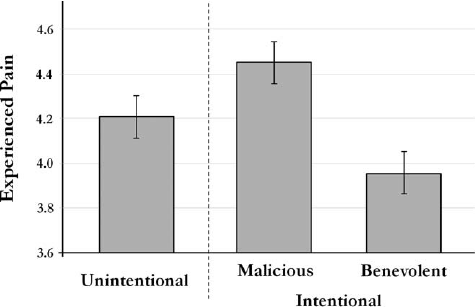

In one study, Gray and team explored whether our judgment of intentionality impacts how we perceive physical pain (operationalized by electric shocks). To test this out, they randomized participants (n=84) into three groups. Each participant was set up with a partner.

Accident condition: Participants thought they were being electrocuted by accident.

Malicious condition: Participants thought they were being shocked on purpose, but for no good reason.

Benevolent condition: Participants thought they were being shocked on purpose, but because their partner was trying to help them win money.

The researchers wanted to see how each group rated their pain levels on a 7-point scale, ranging from “not at all uncomfortable” to “very uncomfortable”?

Stop and think: Would perception of intentionality impact how you would experience physical pain? And if so, how?

Results

Turns out, intentions matter. Even though everyone experienced the same level and frequency of electric shots, perception of positive intent significantly decreased physical pain, whereas perception of malice increased pain.

Takeaway

If the way we read other people’s intentions impacts our experience in the world, then it may be prudent to be deliberate in our communication and interpretation of intentionality.

If, for example, you are about to give someone potentially hurtful feedback, ask yourself:

What are my (positive) intentions?

How will I make them known?

If, on the hand, you are on the receiving end of difficult conversation, ask:

So that I understand where you are coming from, can you share your intentions for telling me X?

Asking questions around intentionality will create greater clarity, soothe the inevitable sting, and increase the likelihood of your message being heard.

A word of caution

While not mutually exclusive, there are instances where thinking about intent can result in inaction. For example, in the case of experiencing microaggressions, thinking about people’s intentions may mollify the hurt and reduce motivation to give feedback in the first place. Therefore, assumption of positive intent, while generally good, needs to be coupled with other considerations (e.g., What’s the cost of inaction?).

Your turn

What insights does this research generate for you?